Guidelines for Creating Accessible Documents for Websites

- Luis Barraza, Amanda Chase, and Elizabeth Sohn

- Sep 22, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 27, 2021

Accessibility Guidelines

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are a set of standards established by the World Wide Web Consortium to make web content accessible for users. Web accessibility means that websites, tools, and technologies are designed and developed so that people with a variety of different needs can use them. More specifically, people can:

perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web.

contribute to the Web.

Providing accessibility to websites and digital documents is a natural progression of the extension and outreach already practiced by ACES throughout the state. Going through these efforts benefits the people that need accessibility and benefits NMSU as well. Designing with accessibility in mind from the start will expand the audience, improve usability overall, as well as reduce the cost and effort of accommodations in the future.

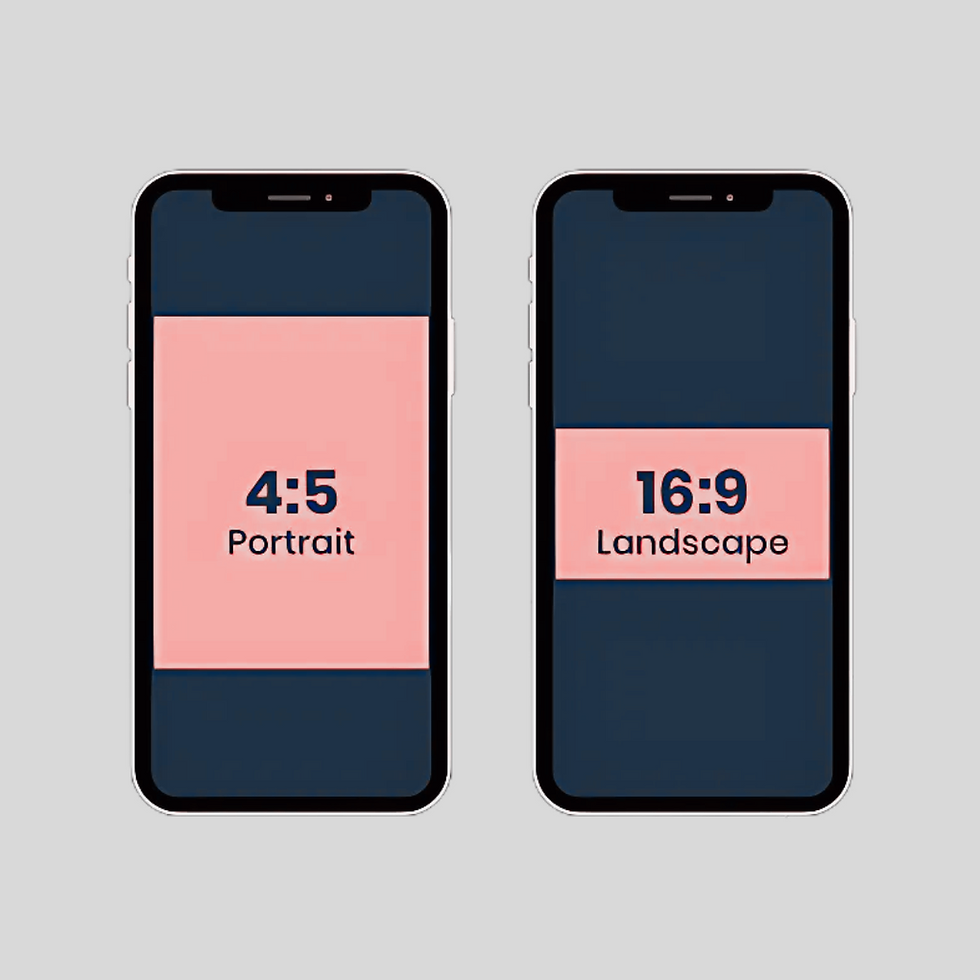

Alternative/ Descriptive Text for Images

Alternative text, usually referred to as alt text, is the description of an image in a document that is not visible on the page but will be read by screen readers commonly used by people with vision impairments. It is used to communicate what the image is to someone who may not be able to see it. It can describe the image, or relay any text that is in the picture.It is good practice when writing alternative text for an image, to ask: Does this image need alt text? Not all images need alt text: some images are simply decorative, and can be marked as such. When looking at an image, ask the questions:

What function does the image serve?

What content does the image add?

What information is the image providing that is not in the main text?

Prioritizing and recognizing what images are vital and what images are there for visual appeal is a subjective judgement but can help save time writing alt text in the long run. The crimson blocks of color and repeating logo seen on many NMSU documents and newsletters are examples of elements that might be tagged as images in a PDF document but can be dismissed as decorative elements: therefore, no one is forced to type “NMSU Logo” to describe the image.

When it comes to writing alternative text, context is everything: Be as concise as possible. Also avoid the phrase “image of…”. The screen reading software will already make it clear that the user has come across an image. For example, if an article or document includes an image of a person, what you say about that image depends on the relationship the image has to the article. If the main text is about the individual in the image, the alt text could just be the person’s name, their title, or if it is an official portrait or painting. Very rarely does the clothing and appearance need to be described unless it is entirely relevant to the main text. Best practice is not to go beyond two sentences. Any text beyond that should be in the main text.

Example of Alt Text for Images:

How to Tag Images in Common Programs

Never use automatically generated alt text to save time. The technology is not quite there yet, and automatically generated alt text is often poorly formatted and incorrect. Because the context of an image matters, and a computer will not be able to extract that automatically, you are likely to spend more time correcting automatically generated alt text than you save by using it.

For more complex images that include data, write the alt text in the body of the document.

Example of Alt Text for More Complex Images:

Recommended Resources:

Charts & Accessibility: This site offers in-depth explanations and strategies to describe complex images with both alt tags and in-body text.

Textual Hierarchy and Layout

Textual hierarchy gives the reader access to important information at the beginning of the piece. When creating textual documents, make sure the layout follows a logical order. You can build textual hierarchy using different Headings found in the ‘styles’ section of Microsoft Word or Google Docs. When you label things as Header 1, Header 2, Body Text, etc., they will have consistent formatting at each level of the hierarchy. Both layout and hierarchy give the reader access to the most important information at the beginning of a document. Layout and hierarchy give the reader a road map of the written piece. A typical layout might be:

Title

Heading 1 (Most important points)

Text

Heading 2 (Still important but not as much)

Text

Heading 3 (Lesser points)

Text

In addition, hierarchy helps readers be able to skim the document while still understanding key concepts.

Further Resources:

Accessible Typography: An informational site that explains the importance of typography and hierarchy in textual documents for screen readers.

Color Contrast and Fonts

We are all on the spectrum of need for vision: some users have excellent vision, some web users may have difficulty with color blindness or low contrast, some may use glasses or need larger fonts, and others may not be able to see at all.

Color contrast is the difference between the color used for text and the color used directly behind the text. The more contrast, the easier the text is to read. Black text on a white background is the best contrast, but if a newsletter or flier uses color or exciting design for pop, it is important to pay attention to color contrast. There are guidelines and formulae for color, and there are also handy tools available that take away any guesswork. Many tools analyze for WCAG 2.0 standards, and the goal should be to pass at least AA standards. Contrast checkers will use the phrases normal text and large text when calculating the contrast. Large text in a document is any font that is over 18pt in size or over 14pt if in bold. When selecting a font, refer back to NMSU branding guidelines and to ACES guidelines for best practices.

Here are some recommended resources:

Sim Daltonism: This app, available on the App Store, allows the user to visualize colors as they are perceived with various types of color blindness such as Deuteranopia, Deuteranomaly, Protanopia, and Protanomaly.

Contrast Checker: This is a web tool for color contrast from WebAIM, a terrific resource for learning about accessibility.

Colour Contrast Analyser: This is a tool you can install for either Mac and PC , and it comes with a handy dropper tool that can analyze any set of colors: Click the picture for the github download.

Planning the colors ahead of creating a new document generally results in better color contrast and a finished document that is easier to read.

Example of text that does not meet WCAG standards

In this image, the contrast between the purple and blue colors is not significant enough. The results from the Colour Contrast Analyzer tell us that this combination of colors does not pass the minimum standard for regular text, nor the enhanced contrast standards for regular text and large text. Because the title is considered large text, it is problematic that it doesn’t meet the large text standard for the enhanced guidelines. It is important the text meets both large text standards, for enhanced guidelines and minimum guidelines.

Example of text that does meet WCAG standards

This is the same image as before; however, the text outlines have been darkened. The use of this dark color provides a more stark contrast between the purple of th e letters and the blue of the background. This new image now passes both the Minimum and Enhanced guidelines for large text contrast.

Accessibility Checkers

Most tools have accessibility support features. Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and Excel all have an accessibility tool. The tool can be found by searching for the word “accessibility.”

A panel will appear on the side where you can fix any detected issues directly.

Sometimes, Microsoft will try to automatically generate alternative text, to mixed results. Always double check the text: Microsoft will often ask for verification. Adobe Acrobat has the most comprehensive tool for accessibility. The tool covers more areas in more depth. Addressing issues found in the Adobe Acrobat checker requires greater familiarity with the program but can be a good yardstick to evaluate a document.

Some documents are more complicated than a few images and text. Do not panic, and do as much as possible. While accessibility features continue to evolve, our goal is to do as much as we can, when we can.

For more questions regarding web accessibility on NMSU ACES Websites, contact Luis Barraza.

Written in collaboration by Luis Barraza, Amanda Chase, and Elizabeth Sohn.